The word. It is a potent instrument of transcendence, channeling energies beyond human comprehension, while simultaneously holding a mirror up for the world to reflect on its triumphant spirit of love, as well as its tragic penchant for self-destruction. Centuries before they were first conveyed as written adaptation, the oral word was the essential method of communication, and as civilization evolved it became a determinant factor in evoking emotions that would inspire and motivate the global community, in means both ill and illuminant, through history’s tumultuous arc.

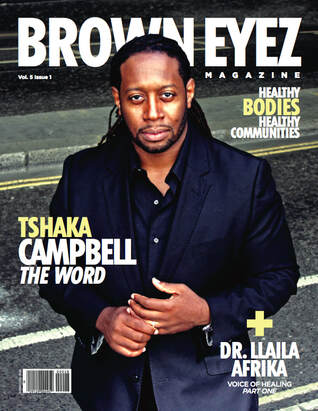

Tshaka Menelik Imhotep is both a student and a purveyor of the spoken word. Referenced largely through the performance circles by his preferred moniker “TarMan Celebrating His Natural Kink”, Tshaka has become one of the more acclaimed and revered artists to emerge from the prodigious pool of spoken word poets within the last decade. An immigrant to the United States at the tender age of ten by way of his native England, Tshaka was raised by his parents in the suburbs of New Jersey, and it was through their early teachings of solidarity that he was educated on the history of his West African roots, his Jamaican lineage, the philosophies of Marcus Garvey and Pan-Africanism, and, especially from his father, the intense power and beauty of language.

“My parents have had a huge influence on me as both a man and as a poet”, Tshaka explains. “Most importantly, I have gotten from them that we are a rich, beautiful and strong people and nothing is gained that is worth keeping without work. I often joke that I am the exact blend of my parents; I get my tenacity, drive and love of language and its power and texture from my dad, but I get my understanding, gentle and communicative nature from my mom. I will be your best friend but your worst enemy. As a poet and as a man, I believe and preach that integrity is your greatest goal and tool. If you are true to your nature, to your cause, yourself and your art, the results of which, although while may not be always the most favorable, are always pure and honest.”

Purity and honesty. It is these two elements of the spoken word at its most intoxicating state that so directly affect the ears and minds of those who listen. The seductive means by which the word can allow one to express his or her joy and pain, remorse and redemption, is enough to illicit a passionate allegiance from even the most jaded audience. Tshaka was smitten by the luring force of poetry at a young age, starting some 15 years ago with a group of peers that he had befriended from Brooklyn, New York. One of these friends had acquired a book of black erotica poetry, and it stimulated the group to start writing poems of their own; twice a month they would hold what came to be known as “Isms at 540”, at 540 Carlton Ave in Brooklyn, and share each other’s writings. Eventually, Tshaka felt the need to express himself outside of the group, and began to attend poetry venues like the Brooklyn Moon, the Nuyorican Poetry Café in Manhattan, and Serengeti Plains in Montclair, New Jersey. He was still developing as a writer, and was taking notes on the various artists he witnessed on his poetry club visits, before he felt comfortable performing his own writings. In 2001, after taking to the stage for the first time to do a reading of one of his poems, he knew he had found his voice.

“I waited in the dimple of a cloud/for a visit from an ancestor,” recites Tshaka in a rendition of his poem “Purpose”, which vividly outlines the trajectory of his journey into becoming, in his own words, a “re-incarnated West African Griot.” “She came to my thoughts dangling from a blade of glass/she had inverted knees and she told tales of walking backwards toward the beginning of journeys…”

In his development as a poet, Tshaka has always attested to the significance of oral traditions; in his work, he is venerated for his mesmerizing cadence and is known for summoning the force of Nyamah, which is translated as “the energy of words”. “Oral tradition is as old as human history itself,” Tshaka asserts. “Before written words we had oral presentation. It’s in our history (and) bloodlines. Words change the world, start wars, bring peace, inspire, etc, etc. And if words can do that, and as poets we control and manipulate words, then we can change the world.”

Tshaka also acknowledges the profound influence of his Jamaican ancestry on his ingenious expression, and the lingering spirit of his forbearers that pervades over all that he creates and all that he is as a representation of his people. “Jamaicans are a truly passionate and expressive people,” exclaims Tshaka, with an exuberance that demonstrates overwhelming pride in his heritage. “That essence is passed down in my genes. I have picked this up through the blood. Jamaicans are a fearless group of individuals and I see that in my work and how I approach the art. In addition, Jamaicans, as with most people of African decent, are rhythmic people. This innate rhythm is weaved into my work and enhances in reliability and style. I approach poetry or a poem as a blank canvas where I paint with words, but not only do the words create the look; so does the texture of paint and the thickness of its application. This part of the artistry comes from my Jamaican background - the texture and thickness of my style and delivery.” The relevance of Tshaka’s heredity to the art in which he adeptly crafts is evident in the closing verses of “Purpose”, in which he describes an encounter with a maternal spirit from his lineal past. “‘…This means,’ she said, ‘that you have a reason/a PURPOSE/a reason to open closed eyelids…a reason to map pathways to human intervention/a reason to defy convention’…She blew me a kiss, that landed on my tongue/in the emptiness of her departure, a baby’s heart began to grow in my mouth/it stretched my tongue and began grabbing at my throat, tearing at my vocal cords/it gave form to a female voice/a daughter of speech that grew to puberty within my opinions, and emerged through my lips/in a puff of air, she named herself: Poetry/and sent me a message through the wind that said ‘if you now understand your purpose, say word’/And I said, ‘Word.’”

Throughout the 2000s, Tshaka steadily built his name through the poetry circuits, and would become one of the art form’s most accomplished and respected performers. He has enjoyed the honor of having multiple awards bestowed upon him for excellence in the arena of performance, including becoming a member of the 2004 Nuyorican Poetry National Poetry Slam Team and the 2006 Hollywood National Champion Slam Poetry team. In addition, he also received the Grand Champion title at the 2005 San Francisco and 2007 Hollywood Championships. This immense success has enabled him to tour and perform internationally, from the famed Apollo Theatre in Harlem, New York to the spoken word venues in cities such as San Francisco. His journey also eventually brought him back to his home country of the United Kingdom, where he currently resides. Tshaka maintains that his excursions across the globe have only served to directly aid in the progression of his art. “Experience is the food that is necessary for artists to sustain themselves,” he attests. “It gives you a more global view of life. I can see how things connect or not, how my narrowed view of things may be supported and or dismantled based on what I have seen in other places. Sort of like, before Malcolm (X)’s pilgrimage; he went to Mecca and saw Muslims with white skin. How could he then continue to preach based on the color of one’s skin after seeing this? But this was not revealed until he travelled and experienced other cultures, other Diasporas, etc. The more I interact with life, the more experiences I have, the more I can reflect that in my work.”

Most recently, the element of inspiration for Tshaka to pause and reflect on through his palette of expression has been his wife and baby daughter. “Having a child and a wife (is) major,” the poet states in a moment of subtle humility. “Your life is not yours anymore –it’s bigger. Your actions affect not just you. Decisions and the ways by which I process those decisions have changed drastically. That’s it in a nutshell – nothing is the same as it was. I can’t get up and travel to wherever to do a show anymore without planning, but I also get to come home from a long working day and see my baby’s smile and hug my wife.” When asked how his wife and child have impacted the content of his writings, he had this to say: “My work/art haven’t changed so much yet—that I can tell at least. I do see that I am writing more about women and varied situations of abuse that are afflicted on them, but not sure if that just a timing thing or triggered by the fact that I have a little girl. I am sure it’s coming though.”

To be certain, what Tshaka can absolutely be sure of is his brilliant star as one of spoken word’s foremost and promising talents continuing its ascendance into the uncharted realms of possibility. In 2006, his pre-eminence as a performance artist firmly established, Tshaka released his debut CD of performance pieces entitled One to global praise; this resounding reception was followed three years later by his sophmore collection, Bloodlines. He has also ventured into publishing entries of his lyrical prose with the books TarMan, a collection of poems, and Muted Whispers, which contains various selections of short stories.

As poet societies from San Francisco to London anticipate the next phase in Tshaka’s enduring metamorphosis, the poet himself is content to allow his purpose to flow from the eternal guidance and wisdom of the great storytellers that color his people’s narrative. The urgency that one hears when listening to Tshaka recite one of his poems underscores how essential the art of language has become in anchoring the world he has created for himself. “Spoken word is a unique vehicle by which you can induce a number of emotions and reaction when done right - and sometimes all at the same time,” he confides. “You can enlighten and inspire, you can arouse and anger, you can make people laugh or have them reflect on their actions. It also works on the poet them self; often I find it’s the only way to get through an issue or to expel demons that I have running rampant in my head. It’s like breathing for me.”

Word.

Tshaka Menelik Imhotep is both a student and a purveyor of the spoken word. Referenced largely through the performance circles by his preferred moniker “TarMan Celebrating His Natural Kink”, Tshaka has become one of the more acclaimed and revered artists to emerge from the prodigious pool of spoken word poets within the last decade. An immigrant to the United States at the tender age of ten by way of his native England, Tshaka was raised by his parents in the suburbs of New Jersey, and it was through their early teachings of solidarity that he was educated on the history of his West African roots, his Jamaican lineage, the philosophies of Marcus Garvey and Pan-Africanism, and, especially from his father, the intense power and beauty of language.

“My parents have had a huge influence on me as both a man and as a poet”, Tshaka explains. “Most importantly, I have gotten from them that we are a rich, beautiful and strong people and nothing is gained that is worth keeping without work. I often joke that I am the exact blend of my parents; I get my tenacity, drive and love of language and its power and texture from my dad, but I get my understanding, gentle and communicative nature from my mom. I will be your best friend but your worst enemy. As a poet and as a man, I believe and preach that integrity is your greatest goal and tool. If you are true to your nature, to your cause, yourself and your art, the results of which, although while may not be always the most favorable, are always pure and honest.”

Purity and honesty. It is these two elements of the spoken word at its most intoxicating state that so directly affect the ears and minds of those who listen. The seductive means by which the word can allow one to express his or her joy and pain, remorse and redemption, is enough to illicit a passionate allegiance from even the most jaded audience. Tshaka was smitten by the luring force of poetry at a young age, starting some 15 years ago with a group of peers that he had befriended from Brooklyn, New York. One of these friends had acquired a book of black erotica poetry, and it stimulated the group to start writing poems of their own; twice a month they would hold what came to be known as “Isms at 540”, at 540 Carlton Ave in Brooklyn, and share each other’s writings. Eventually, Tshaka felt the need to express himself outside of the group, and began to attend poetry venues like the Brooklyn Moon, the Nuyorican Poetry Café in Manhattan, and Serengeti Plains in Montclair, New Jersey. He was still developing as a writer, and was taking notes on the various artists he witnessed on his poetry club visits, before he felt comfortable performing his own writings. In 2001, after taking to the stage for the first time to do a reading of one of his poems, he knew he had found his voice.

“I waited in the dimple of a cloud/for a visit from an ancestor,” recites Tshaka in a rendition of his poem “Purpose”, which vividly outlines the trajectory of his journey into becoming, in his own words, a “re-incarnated West African Griot.” “She came to my thoughts dangling from a blade of glass/she had inverted knees and she told tales of walking backwards toward the beginning of journeys…”

In his development as a poet, Tshaka has always attested to the significance of oral traditions; in his work, he is venerated for his mesmerizing cadence and is known for summoning the force of Nyamah, which is translated as “the energy of words”. “Oral tradition is as old as human history itself,” Tshaka asserts. “Before written words we had oral presentation. It’s in our history (and) bloodlines. Words change the world, start wars, bring peace, inspire, etc, etc. And if words can do that, and as poets we control and manipulate words, then we can change the world.”

Tshaka also acknowledges the profound influence of his Jamaican ancestry on his ingenious expression, and the lingering spirit of his forbearers that pervades over all that he creates and all that he is as a representation of his people. “Jamaicans are a truly passionate and expressive people,” exclaims Tshaka, with an exuberance that demonstrates overwhelming pride in his heritage. “That essence is passed down in my genes. I have picked this up through the blood. Jamaicans are a fearless group of individuals and I see that in my work and how I approach the art. In addition, Jamaicans, as with most people of African decent, are rhythmic people. This innate rhythm is weaved into my work and enhances in reliability and style. I approach poetry or a poem as a blank canvas where I paint with words, but not only do the words create the look; so does the texture of paint and the thickness of its application. This part of the artistry comes from my Jamaican background - the texture and thickness of my style and delivery.” The relevance of Tshaka’s heredity to the art in which he adeptly crafts is evident in the closing verses of “Purpose”, in which he describes an encounter with a maternal spirit from his lineal past. “‘…This means,’ she said, ‘that you have a reason/a PURPOSE/a reason to open closed eyelids…a reason to map pathways to human intervention/a reason to defy convention’…She blew me a kiss, that landed on my tongue/in the emptiness of her departure, a baby’s heart began to grow in my mouth/it stretched my tongue and began grabbing at my throat, tearing at my vocal cords/it gave form to a female voice/a daughter of speech that grew to puberty within my opinions, and emerged through my lips/in a puff of air, she named herself: Poetry/and sent me a message through the wind that said ‘if you now understand your purpose, say word’/And I said, ‘Word.’”

Throughout the 2000s, Tshaka steadily built his name through the poetry circuits, and would become one of the art form’s most accomplished and respected performers. He has enjoyed the honor of having multiple awards bestowed upon him for excellence in the arena of performance, including becoming a member of the 2004 Nuyorican Poetry National Poetry Slam Team and the 2006 Hollywood National Champion Slam Poetry team. In addition, he also received the Grand Champion title at the 2005 San Francisco and 2007 Hollywood Championships. This immense success has enabled him to tour and perform internationally, from the famed Apollo Theatre in Harlem, New York to the spoken word venues in cities such as San Francisco. His journey also eventually brought him back to his home country of the United Kingdom, where he currently resides. Tshaka maintains that his excursions across the globe have only served to directly aid in the progression of his art. “Experience is the food that is necessary for artists to sustain themselves,” he attests. “It gives you a more global view of life. I can see how things connect or not, how my narrowed view of things may be supported and or dismantled based on what I have seen in other places. Sort of like, before Malcolm (X)’s pilgrimage; he went to Mecca and saw Muslims with white skin. How could he then continue to preach based on the color of one’s skin after seeing this? But this was not revealed until he travelled and experienced other cultures, other Diasporas, etc. The more I interact with life, the more experiences I have, the more I can reflect that in my work.”

Most recently, the element of inspiration for Tshaka to pause and reflect on through his palette of expression has been his wife and baby daughter. “Having a child and a wife (is) major,” the poet states in a moment of subtle humility. “Your life is not yours anymore –it’s bigger. Your actions affect not just you. Decisions and the ways by which I process those decisions have changed drastically. That’s it in a nutshell – nothing is the same as it was. I can’t get up and travel to wherever to do a show anymore without planning, but I also get to come home from a long working day and see my baby’s smile and hug my wife.” When asked how his wife and child have impacted the content of his writings, he had this to say: “My work/art haven’t changed so much yet—that I can tell at least. I do see that I am writing more about women and varied situations of abuse that are afflicted on them, but not sure if that just a timing thing or triggered by the fact that I have a little girl. I am sure it’s coming though.”

To be certain, what Tshaka can absolutely be sure of is his brilliant star as one of spoken word’s foremost and promising talents continuing its ascendance into the uncharted realms of possibility. In 2006, his pre-eminence as a performance artist firmly established, Tshaka released his debut CD of performance pieces entitled One to global praise; this resounding reception was followed three years later by his sophmore collection, Bloodlines. He has also ventured into publishing entries of his lyrical prose with the books TarMan, a collection of poems, and Muted Whispers, which contains various selections of short stories.

As poet societies from San Francisco to London anticipate the next phase in Tshaka’s enduring metamorphosis, the poet himself is content to allow his purpose to flow from the eternal guidance and wisdom of the great storytellers that color his people’s narrative. The urgency that one hears when listening to Tshaka recite one of his poems underscores how essential the art of language has become in anchoring the world he has created for himself. “Spoken word is a unique vehicle by which you can induce a number of emotions and reaction when done right - and sometimes all at the same time,” he confides. “You can enlighten and inspire, you can arouse and anger, you can make people laugh or have them reflect on their actions. It also works on the poet them self; often I find it’s the only way to get through an issue or to expel demons that I have running rampant in my head. It’s like breathing for me.”

Word.